Below are some instances where I overcame my writer's block; a complete publication list can be found in my ORCID profile or the full CV. Many of these are available open access; if you can't get hold of a copy, drop me an email.

Micro-mobilities and belonging

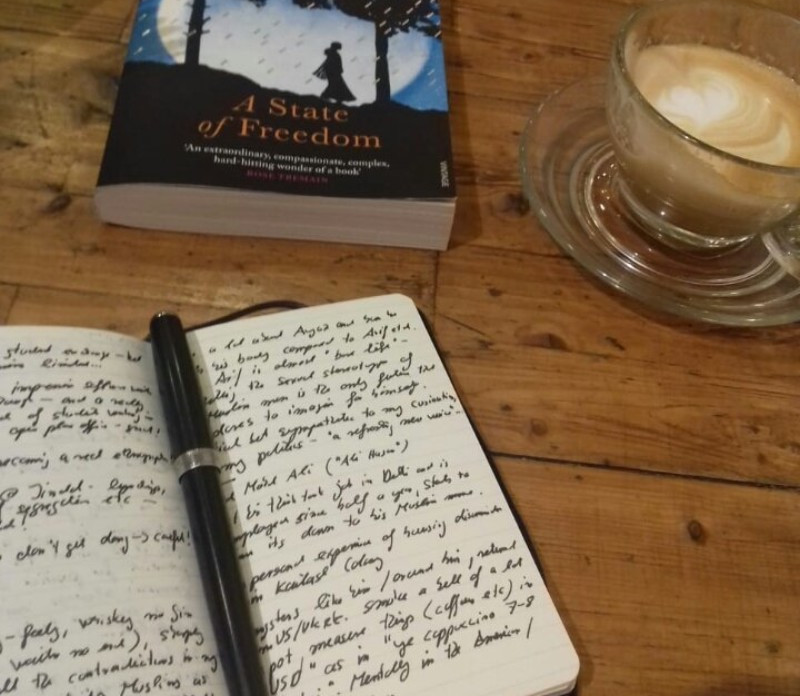

Spatial mobility is often considered on large geographical scales: people move from distant villages to global cities, they migrate from one country to the next, or even to a whole new continent. Such large-scale migration comes with shifts in economic position, social status and cultural exposure, shifts that condition new figurations of belonging - or so the argument goes. In contrast, I ethnographically follow the looping movements of three young men in Lucknow who aspire to migrate but remain stuck, who find a whole new world by crossing the river, whose small steps reflect big dreams. As the world grapples with ‘lockdowns’ and ‘stuckedness’ in the Covid-19 pandemic, I sketch their aspirations, mental maps and the material restraints that condition their trajectories. Through them, I demonstrate how looping micro-mobilities - cruising through the night, dancing on stage, riding one's bike - can be as effective in fostering new figurations of belonging as the grand movements emphasized in literature on migration. I further explore which spaces enable and contain such micro-mobilities, rediscovering the potency of urban settings to make people feel at home and out of place in small but important ways.

Susewind, R. (2021). Dreaming in the shadow of history: Micro-mobilities and belonging in Lucknow. Contemporary South Asia 49(4), 500-513.

Public sphere and public space in urban India

Public space comes under threat, is contested as much as shared, an arena for power and hegemony, leaving little hope for interaction across social divides. At the same time, each reincarnation of our fragmented public sphere necessarily builds on historical precedent, inadvertently inscribing public space with fresh hope as it expands the scope of the term’s original promise. Over time, this process creates iconic infrastructure such as the Rifah-e Aam Club, the “Club for the public good” in Lucknow, North India. From the initial stirrings of associational culture under British colonialism through key moments of the national movement down to today’s goonda raj, or rule of thugs, this unruly space came to host the most unlikely republic of letters, reuniting a public across time and space that often seems irredeemably fragmented. It is when buildings like this acquire a life of their own that cities realise their creative promise.

Susewind, R. (2020). Rifah-e Aam Club, Lucknow: Public sphere and public space in urban India. Geoforum, 109, 67-77.

Degrees of segregation and the elusive ghetto

In India, the country with the third largest Muslim population in the world, residential segregation along religious lines has long been of concern. Many go so far as to speak of the large-scale ‘ghettoization’ of Muslims, a trend commonly attributed to the state’s negligence towards this religious minority and prolonged histories of so-called ‘communal’ violence between religious groups. Others emphasize long-standing pattern of residential clustering in enclaves and claim that these have always been voluntary. Both the ghetto and the enclave are usually considered highly segregated spaces, though. This paper complicates such views through an in-depth engagement with the seminal ethnographic volume Muslims in Indian Cities, edited by Laurent Gayer and Christophe Jaffrelot. Based on novel quantitative estimates of religious demography, I contrast and compare the same 11 cities studied in their book – Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Jaipur, Lucknow, Aligarh, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Delhi, Cuttack, Kozhikode and Bangalore – using statistical indices of segregation. This comparison with the ethnographic ‘gold standard’ shows that the mere extent of segregation is an insufficient shortcut to the phenomenon of ghettoization: a ghetto actually need not be highly segregated and a ‘mixed area’ can be surprisingly homogenous. Consequently, I argue that one should not only distinguish between voluntary and forced clustering but also consider the wider ‘mental maps’ through which inhabitants experience, perceive and judge their city. Such mental maps specifically help to uncover historical trajectories, feelings of insecurity and the future expectations of people regarding their cities – irrespective of quantitative degrees of segregation.

Susewind, R. (2017). Muslims in Indian cities: Degrees of segregation and the elusive ghetto. Environment and Planning A, 49(3), 1286-1307.

Spatial segregation, real estate markets and the political economy of corruption

A number of scholars have argued that discrimination against Muslims in India’s urban housing markets stems from long histories of Hindu–Muslim ‘communal’ violence, and that the resulting antagonism and discrimination against Muslim tenants and homebuyers leads to their permanent ‘ghettoisation’. In such accounts, the state is portrayed as absent and unable to provide ethnic minorities with a sense of security, so that disenfranchised Muslims seek out the ‘safety in numbers’ of segregated and often traditional neighbourhoods, even when urban housing markets provide updated and modern accommodation elsewhere. Based on official property registration data and ethnographic fieldwork in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, I complicate this narrative, focusing on the productive practices of networking and collusion that enable a veritable building boom in ‘traditional’ Muslim neighbourhoods. The article shows that proximity to bureaucrats, the relative electoral strength of Muslims, and the existence of waqf property result in lower expenses for corruption and thus higher profit margins for Muslim developers in traditional Muslim areas. Irrespective of discrimination elsewhere, this arguably creates positive incentives for Muslims to stay put, and thus demonstrates that their continued segregation does not necessarily indicate blanket disenfranchisement – but rather a differential incorporation in the political economy of collusion.

Susewind, R. (2015). Spatial segregation, real estate markets and the political economy of corruption in Lucknow, India. Journal of South Asian Development, 10(3), 267-291.

Sectarian conflict and the middle classes

On 16 January 2013, a Sunni real estate developer opened fire at a Shi’a religious assembly in Wazirganj, a mixed neighbourhood in old Lucknow, India, killing one and injuring two. At its core, this was a business rivalry gone awry, but was soon labelled the ‘Wazirganj Terror Attack’ by Shi’a activists. Demonstrations were staged, politicians were arrested, and religious gatherings were invigorated. Based on 17 months of ethnographic fieldwork, this paper considers why the attack took place and why it escalated. The political economy of real estate and local politics are argued to have motivated the attack, but the attackers miscalculated and lost control of the incident. The subsequent escalation can only be understood in light of Shi’a clerical competition over new moral registers and an emerging middle class morality that replaces ethical concern for solidarity with narrow codes of ‘proper’ conduct. This underlines the importance of intra-group contestation to intergroup conflict, and the limits of purely instrumentalist explanations of sectarian violence.

Susewind, R. (2015). The "Wazirganj terror attack": Sectarian conflict and the middle classes. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 11, 1-45

Islamicate Lucknow today

Lucknow, a city once dominated by Shi’a nawab rulers, is now known for elites’ nostalgia for Islamicate pasts and masses seeking better futures. This special issue builds interdisciplinary dialogue about a city overwhelmingly represented in historical accounts and emplaces Lucknow within recent investigation of urban India in which the city of nawabs is largely absent. Focusing on old city Lucknow where Muslims still demographically predominate, our introduction blends ethnographic exploration of cultural memory with new statistical data on old city’s changing population, socioeconomic ‘backwardness,’ and segregation. We frame Lucknow’s Islamicate old city in contemporary times as a place where north India’s beleaguered Muslim minority negotiates between their remembered cosmopolitan past and a present burdened by structural violence and communal riots – blending (rather than choosing between) modernity and tradition, cosmopolitanism and provinciality, melancholia and aspirations, history and future.

Susewind, R, Taylor, C. (2015). Islamicate Lucknow today: historical legacy and urban aspirations. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 11, 1-42.

What's in a name?

Fine-grained data on religious communities are often considered sensitive in South Asia and consequently remain inaccessible. Yet without such data, statistical research on communal relations and group-based inequality remains superficial, hampering the development of appropriate policy mea- sures to prevent further social exclusion on the basis of religion. The open- source algorithm introduced in this article provides a workaround by prob- abilistically exploiting the communal connotations of names; it transforms name lists—which are readily available—into a new source of demographic data. The algorithm proves highly accurate in identifying Muslim population shares in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, but could be employed more widely across South Asia. It potentially enables more detailed analyses in economics, development studies, and political science as well as better sampling procedures in sociology and anthropology. This article describes the algorithm, evaluates its accuracy, reflects on ethical implications, and introduces a sample data set; the software itself is available in an online sup- plement to this article.

Susewind, R. (2015). What's in a name? Probabilistic inference of religious community from South Asian names. Field Methods, 27(4), 319-332.

Spatial variation in the "Muslim vote"

In this paper, we propose to reconcile the controversial debate on Muslim "vote banks" in India by shifting the spatial focus from state-wide assessments to the level of constituencies. At the example of Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh in the 2014 general elections, and using an innovative booth-level ecological inference model, we show that Muslims might indeed vote en bloc for or against certain parties, but they tend to do so in a much more localised way than previously assumed. While public Muslim support for the BJP did not translate into electoral support in most places, there are important exceptions to this trend – and at least in the case of Uttar Pradesh, their support for competing parties followed a fairly complex spatial pattern. We further explore this spatial variation in Muslim vote pattern by looking at the moderating impact of minority concentration, violent communal history, and ethnic co-ordination and conclude with a call for more disaggregated research.

Susewind, R, Dhattiwala, R. (2014). Spatial variation in the "Muslim vote" in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, 2014. Economic & Political Weekly, 49(39), 99–110.

Being Muslim and working for peace

Muslim peace activists in post-conflict Gujarat experience the `ambivalence of the sacred' as a personal dynamic; as faith-based actors, secular technocrats, emancipating women and doubting professionals, they struggle for a better future in diverse and sometimes surprising ways. By taking their diversity seriously, my book sharpens the distinction between ambivalence and ambiguity, and provides fresh perspectives on religion and politics in India today.

Susewind, R. (2013). Being Muslim and working for peace: Ambivalence and ambiguity in Gujarat. New Delhi: Sage.

Opfer und Aktivistin

Recourse to religion can escalate as well as de-escalate intergroup conflict – so far the emerging academic consensus. But the "ambivalence of the sacred" (Appleby 2000) concerns not only violent or non-violent movements or ideologies, it is also experienced on the micro-level of religious identities and individual agency. This article demonstrates at the example of two female Muslim peace activists' biographical narratives and psychometric profiles how the ambivalence and ambiguity of religion towards violent conflict unfolds as a decisively personal dynamic. Both women struggle with and fight for religion in Gujarat, India – and both experience their own Muslimness as ambivalent and ambiguous. Their narratives further emphasize the relevance of explorative empirical methods on the personal micro-level for an adequate understanding of religio-political conflict.

Susewind, R. (2011). "Opfer" und "Aktivistin": Zwei Muslima aus Gujarat ringen mit der Ambivalenz des Sakralen. Internationales Asienforum, 42(3-4), 299-317.